Growing a stronger political ecosystem in agroecology through the vanguard function

Thinking with Rodrigo Nunes' 'Neither Vertical Nor Horizontal' towards a stronger, relational, agroecological political ecosystem that supports its own vanguards

Agroecology is understood as inherently political. This is one of its main distinguishing features from regenerative agriculture, which it is often conflated with. This acts as important firewall, but no firewall is unimpeachable. As regenerative agriculture has always been a form of greener capitalism, agroecology, as its antithesis, has long been imagined as a way to overcome the rule of capital. But ideas and movements morph over time and agroecology is no exception. After decades of right wing and capitalist dominance in politics it is easy to collapse into a position of so-called pragmatism, whereby the idea is just to reform the status quo rather than overthrow it.

This is a strategy borne of despair capitalised upon by corporate interests. And so today we have many concerns around the co-option of agroecology. I think some of these concerns arise from a conflation of regenerative agriculture and agroecology, something to tease apart another time, but I also think the idea of co-option lets agroecology off the hook. It suggests a nefarious, opportunistic outside actor that has worked the wonders of hegemonic forces, which is partly true. Although I think reality is closer to large fractions of agroecology having sold itself out due to a misplaced belief in the necessity of so-called pragmatism1. Further, I think as agroecological NGOs and academia have become career paths in and of themselves, work that can feel virtuous and progressive, so-called pragmatism has become a means to an end for agroecology as a career path.

Both NGOs and academics have to compete for funding from liberal sources and thus the ideology of liberal capitalism reproduces itself through these actors. It’s a web that agroecology is caught within and is potentially suffocating from. To me it feels like large fractions of agroecology have become stagnant. I don’t think this means that all of us needing to find employment within these institutions means we are doomed to sell out the radicalism of the agroecology movement, but it does mean we all need to engage in continuous critical reflection and act outside of our paid work.

Even if you disagree with my hunch that agroecology is becoming stagnant and moving away from its anti-capitalist stance, then at least we might agree that the movement needs to continue growing and building its power. To do that it must continue to propagate itself. To chart a path forward I’ll turn to Rodrigo Nunes’ Neither Vertical Nor Horizontal: A theory of political organisation, a book published in 2021, which I’m currently reading and finding very generative to think through2.

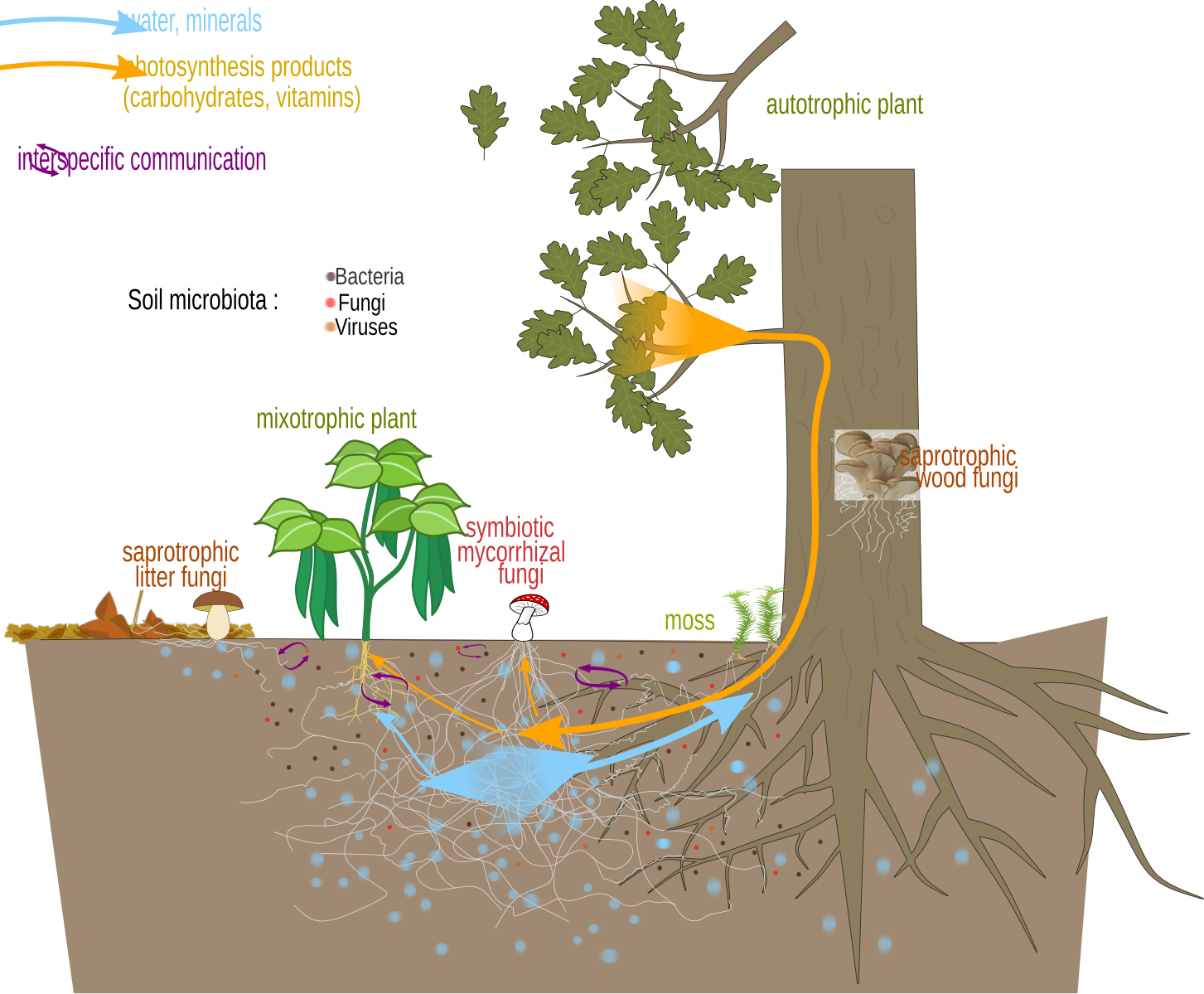

Overall, the book contains, I think, a sophisticated and sympathetic engagement with various left tendencies, strategies and tactics. In particular with the overarching ideas around attempts at horizontality and of more consciously hierarchical or centralised forms of politics. What he argues throughout the book is the need to conceive of political organisation as a relational ecosystem, as something more akin to a mycelial network. It seems apparent to me that such a metaphor should find fertile ground within agroecology.

Organising Nodes

Networks are made up of organising nodes that fulfill different functions within the wider network. A smaller node might be a small group, a local project, even a website or podcast. A larger node might be a large festival/conference or large NGO, which itself will possess many organising nodes. At one level of abstraction agroecology itself is just a cluster of nodes within a wider left anti-capitalist political ecosystem. Nunes’ uses the idea of thinking fractally.

A problem with a landscape sustained by few funding sources is that competition develops between these various nodes. The funding world in agroecology is far from infinite. Competition breeds suspicion and possessiveness and leads to monopolisation. Differences that could otherwise be tolerated become intractable. To be sure I don’t want to suggest the liberal conceit of there being no distinction between friend/enemy, right/wrong, just/unjust etc. These are judgement calls that have to be struggled for. But clearly at times there can also just be a healthy difference of opinion that can be respected. In the book, Nunes’ points to the need for generative tension and internal plurality within a political ecosystem.

More reflexive political ecosystems would find value in this tension and engage in a process of considering the health of the overall ecosystem beyond the dominance of a singular (cluster of) organising node(s). Nunes’ doesn’t fall for conceptualising a ‘flat ontology’3 of power — clearly power is differentially distributed throughout the network. Those individuals and those nodes who are performing what he describes as occupying the leadership function particularly need to engage in reflexivity. To what degree are they serving the movement as a whole or their own narrower interests?

I think one way of analysing the proliferation of new organising nodes within agroecology in recent times is that the previous organising nodes haven’t been able to find a solution to internal contradictions. An inherent contradiction of the cross-class movement for agroecology is its own class composition being broadly based on a dichotomy of land owners and land workers. Those with class power have to consider class suicide as a powerful path forward for the health and growth of the entire ecosystem. A move from valorising the ownership of land to a post-ownership ideal that is guided by the desires and demands of the landless.

Also, I’m not suggesting the proliferation of new organising nodes is a weakness, but the strength of agroecology as a movement depends upon strengthening and supporting these new nodes. Nunes’ conceives of a movement as itself made up of multiple ‘non-totalisable’, overlapping networks. The more connections a node develops the more likely it will come to dominate and attract new connections. This over time can stifle the incentive to innovate and take the initiative.

The Vanguard Function

‘The vanguard-functions’ role is not to explain to people what their desire is, let alone what it ought to be, but to listen to the stirrings of that desire, to incite it, to bring it out into the open; to help giver it shape, to help people draw consequences from it.’ (Nunes, p211)

Another important intervention made by Nunes is to introduce the idea of the vanguard function. Rather than seeing vanguardism as an end in itself it posits that the vanguard function is a necessary role within a wider ecosystem that is premised on a group of people taking initiative and attempting to find a new direction. Sometimes successful, sometimes not. The vanguard makes a wager, tests a hypothesis. He explains that, legitimacy, rather being pre-ordained by apriori claims to being more radical, is granted upon the ability of the vanguard to draw others with them, and by definition this ends up halting its position in the vanguard i.e. it is no longer a vanguard, but a new organisational node in itself.

A question for agroecology at this time is will it support its own vanguards or will those with the power to do so starve them of support and conserve vested interests? Movements wax and wane according to such decisions. Capacity over the long term, in this world, is often dictated by a level of funding. A vanguard can, for a certain amount of time, clear a path with enthusiasm alone but there will become a time when funding is required to sustain its health and growth and secure its position as a new organising node.

Can agroecology as a movement de-monopolise? Successfully answering this question is core to whether it can succeed in coming years. Success that is ultimately determined by agroecology’s contribution to overcoming fascism, overthrowing capitalism, and building agroecology.

I’m going to keep saying so-called pragmatism, because I do not want to concede that it is pragmatic - I think it might superficially appear as pragmatic but is in fact the opposite of pragmatic.

In particular, I’m drawing on chapter five, Elements for a Theory of Organisation I: Ecology, Distributed Leadership, Organising Cores, Vanguard-Function, Diffuse Control, and chapter six, Elements for a Theory of Organisation I: Platforms, Diversity of Strategies, Parties

Some have more power, some have less, and power relations are differentiated within an overarching structure laid by imperialist capitalism

This really resonated, especially the call for building shared political culture and deeper, more connected organising. It’s so easy to get stuck in reactive mode, especially in times of constant crisis, but this piece is a powerful reminder that long-term change comes from relationships, trust, and collective purpose. Grateful for this perspective, it’s exactly the kind of thinking we need more of!

You have me thinking of back to the landers who buy farms to retire from "busy" lives, those who buy farmland to preserve it for local meat and vegetable production, and those interested in advancing zoning laws to preserve farmland.