Farms failing to accumulate

Utilising economic data for English agriculture I explore the failure of English farms to valorise their capital and what this might mean for posing an ecosocialist alternative to capital

If a farm is failing to valorise their capital (failing to enlarge their wealth over time) then why do they continue farming? They could sell the farm and invest the money in stocks, shares, property etc. and make enough money to live off without needing to work another day again (no being a landlord isn’t a job). If the farm has around £2 million in assets and they can secure investment returns of around 5% then that represents untaxed income of around £100,000 per year (more than double what the average farm earns each year). This is the question I’ve been pondering the last few weeks and in this piece I offer some initial rough ideas.

I’m currently researching agricultural economic data for England as part of what I hope will form the basis for a new research article. Something that struck me was a measure they use called Return on Capital Employed (ROCE), which is typically used in the world of accounting and investing to assess a company’s performance. It can tell you whether the company is worth investing in or not. If a company only returns £2 for every £100 invested, then you should find a different option, particularly when inflation is higher than 2% (currently globally around 7.5% and in the UK around 3%). But if a company’s ROCE is around 10% then you’re significantly valorising your capital base every year. It means the value of your assets are increasing — you’re getting richer. And wealth in this world is significantly driven by the ability to draw a rent (or income) on your assets. If you have large enough assets you don’t need to work, or it reduces how much money you need to earn from your work. Hence why people are investing their wealth into property, renting it out, and living off the work of others — a straightforwardly parasitic economic relationship.

The Department of Environment, Farming and Rural Affairs (Defra), defines ROCE as a ‘measure of the return that a business makes from its available capital.’ This figure includes all income before interest and taxes and deducts an imputed value for unpaid labour. So this ROCE figure as I understand it would be for needs beyond the basic reproduction of the household, hence it being a measure of available capital to invest.

As you can see, last year, even when the value of the land wasn’t accounted for, the majority of farms in England were not valorising their capital. Only General Cropping1 and Specialist Pigs and Poultry are actually valorising their capital.

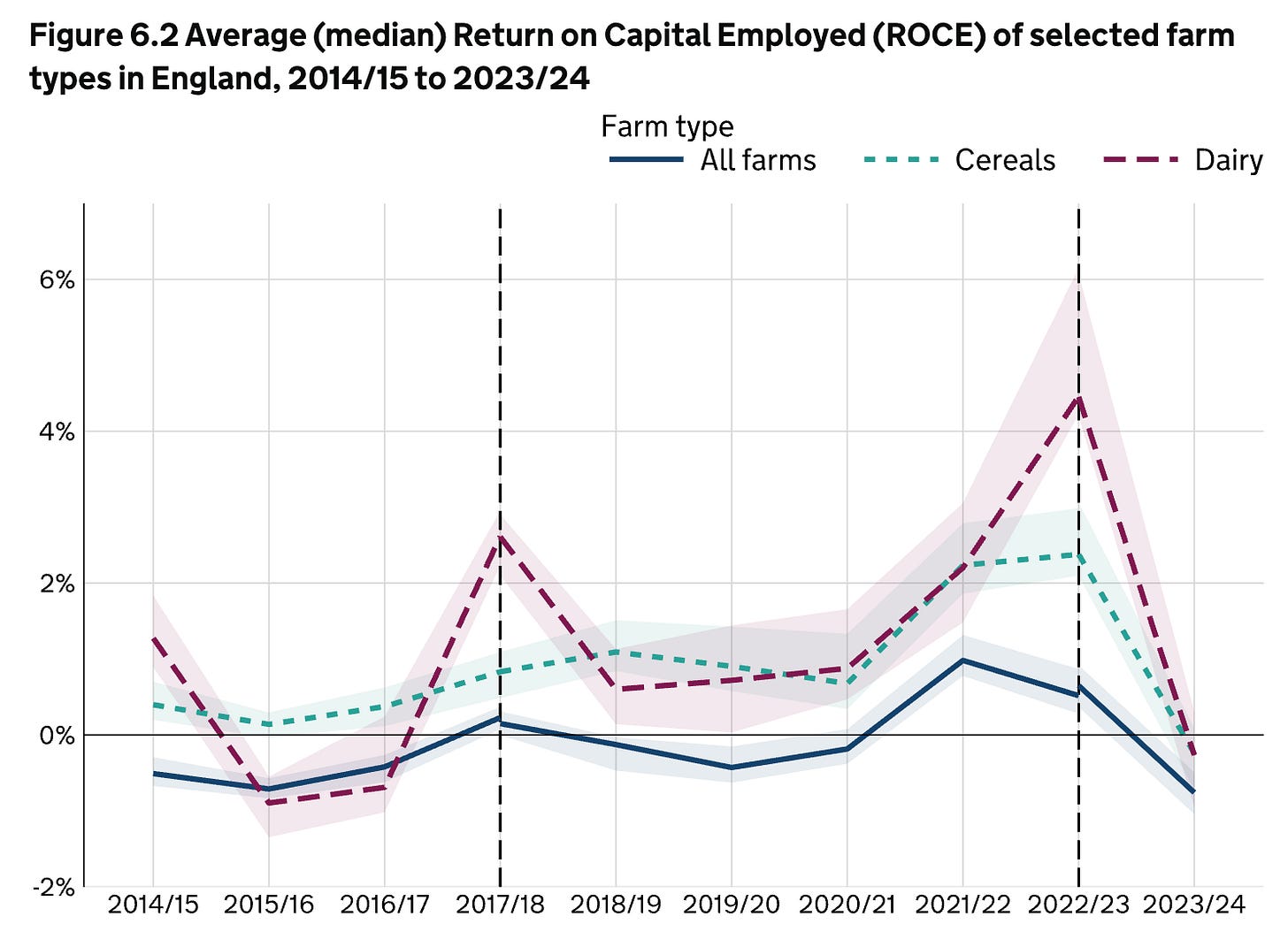

Over a longer time span it looks roughly the same:

Even the peaks for dairy do not represent a real terms return on capital.

And the following is the oldest data I can find and yet again it shows a loss for every year since 2013 in both nominal terms and real terms — and a loss in real terms for the entire series. Real terms means when inflation is taken into account (as opposed to nominal terms which doesn’t take inflation into account). Inflation in the UK, as measured by the consumer price index, is at around 3%. So if you’re not earning at least 3% on your capital, then your capital base is devalorising over time. Project that over a decade and it means that your assets are worth less in ten years time than they are today.

The next chart shows that at 84% of farms are not valorising their capital in real terms.

I think these graphs show that if a farm owner was to look at their capital in a rational economic manner (the mythical creature of classical economics) they would dispose of the farm and invest it just about any other investment option. For comparison, the S&P 500, which tracks the 500 largest stocks in the US, has historically returned around 10% in nominal terms. Amazon also averages at 10%. Elbit Systems, Israel’s largest arms manufacturer who profit from genocide, will provide you with a blood-soaked 8% return (although that’s below the industry average of 12%). Bombs are a better bet than bread in this world of capitalist imperialism.

As I ponder on these charts and their significance it suggests to me that capital doesn’t provide a strong future for most farmers in England — and by extension the rest of the UK, given that the state of things in Wales, for example, is worse not better (just the data is patchier than England). They’re going to see their asset base eroded and their ability to compete and turn a profit further decline over time. As inflation continues farms continue to suffer a real terms decline in their asset wealth. And I see little evidence that incomes for farmers look set to improve in the future. The government wants to reduce investment in farming (in real terms its declined by 30% in the last decade), rises in farmgate prices rarely rise above the rising costs of production, and even today when beef and lamb prices are at historical highs, the UK is in the processes of signing a trade deal with the US, one of the world’s largest beef producers. Certain sectors may spike for a year but the long term average for most farms is poor.

What I think we’re seeing is a polarisation of the farming petite bourgeoisie, so that only around 10% or less are actually functioning as successful capitalist enterprises. Every year growing economic pressures bites at the bottom percentages, forcing farms to sell up. By and large there are two buyers: for non-agricultural use like renewables, forestry or rewilding/conservation, and larger farms who are able to stay in the game longer by further intensifying or reducing costs in other ways.

Farmland has also stopped valorising beyond inflation. For example, even despite all the extra competition for land right now, land prices have plateaued again:

In the last decade the price of land has barely gone up by 10%, despite significant inflation. In other words, land is not valorising in real terms.

Building an effective ecosocialist alternative

Why might any of this matter? If a farm has something like £2-3 million of assets that doesn’t make them poor and if they are earning enough to just about stay in business then surely that’s what matters? Over time if a farm business isn’t accumulating capital it means they’re eating away at the capital they require to reinvest in the farm and further modernise it according to the competitive demands placed upon them by capital.

For example, to be profitable in an industry like dairy these days requires ever-increasing levels of labour productivity (and increasing standards of infrastructure to keep up with environmental and welfare regulations) given the extremely tight margins. There is potentially a bigger crisis facing cereal farmers as the price of wheat is currently well below costs of production, and the impending trade deal with the US will only make this worse given that it will depress demand for British cereals in the form of bio-ethanol and will likely allow for the importing of US wheat.

All this is to say the pressures of achieving profit in a constrained global economy is going to squeeze the farmers at the bottom. Many will be able to continue for years I’m sure but over time a lack of investment will lead to farms falling behind — capitalist competition will deem them surplus to capital’s requirements.

The UK’s Secretary of State for the Environment, Farming and Rural Affairs, Steve Read, continues to preach a mantra of profitability for British farms. He claims Labour will help them restore profitability (as they do everything possible to undermine this!). But how? British farming has long been dependent on subsidy payment and that subsidy is no longer a ‘subsidy’ for many farms but an absolute necessity for staying in business — in order to produce food. He’s talked about diversification but how many more milk vending machines and shepherd’s huts can the countryside take? Carbon and biodiversity markets might work for some but the demand is nowhere near the level required to take on the slack of the subsidy scheme. Bar the most intensive or the most cost efficient farms it’s hard to see how British farms will manage to keep apace. Given that the UK already imports nearly half of its food, for me, it’s hard to see how this doesn’t decline further. Worryingly, cereals are particularly exposed to this growing crisis of profitability and climate change. Last spring arable farmers were struggling to get on the fields because it was too wet and this year it’s the total opposite — their crops are starving with thirst amidst a serious drought.

Plenty of farms will find a way to keep going — average levels of debt are actually low across the sector, regenerative agriculture techniques reduce costs by a percentage, and perhaps more move into more capital-intensive sectors like specialist pigs and poultry as these rely on a large amount of imported feed from places where it can be produced more cheaply. Although climate breakdown severely threatens that last one. Some will find some form of diversification, probably renewable energy for those who are in locations where this is an opportunity.

You could argue that capitalism has already failed many farms in Britain in the last century. Whilst the loss of farms is receiving attention right now, the reality is that, roughly speaking, farm numbers in the last few decades have halved as farm sizes have doubled. This trend seems likely to continue apace but within an overall context of reducing food production2. The farmers I speak to all voice their desire to be food producers and rarely is their business posed in financial terms beyond the basics of being forced to run a profitable business in order to continue producing food. Maybe there’s an opening here. My gambit is that this crisis provides an opportunity for ecosocialist agrarian policy to support alternatives — of which there are plenty of policy options — to help keep farms producing food.

The less food Britain produces the more food we must import which, generally-speaking, means more pressure on the land and labour of the global south. Therefore anti-imperialism requires us to increase domestic food production, not see its further decline. That said, that doesn’t mean supporting a status quo that imports vast amounts of feed from degraded ecosystems in places like the Amazon. Or the continued reliance on super-exploited labour and bad working conditions. This isn’t an argument for the status quo. It’s an argument for using (and addressing) the crisis to offer a new path, an alternative agreement, that would lead to an increase in domestic food supply, whilst reducing Britain overseas land footprint, and improving working conditions on farms.

But none of that can be achieved within the logics and limits of capital. Only ecosocialism shows an alternative that can help humans and non-humans alike flourish. As a transitionary programme that alternative will include revamping and rebuilding council farms to offer a competitive public option to private land/rental markets, extending full workers’ rights to all farm workers regardless of the passport they hold, financial support for agricultural green transitions, better integration into public provisioning, and plenty more. The struggle for which begins in the here and now.

And in case you missed it the far right are offering their version of an ‘alternative’ by conjuring and propagating conspiracy theory that blames immigrants and net zero. I’ll have an article coming out on that soon. So we really need to get cracking with effectively building our own alternative.

As I said in intro these are really initial thoughts and ideas and I will be spending the coming months pursuing some of this further. I welcome all comments and feedback on the above.

From Defra: General cropping: farms with over two-thirds of their total SO in arable crops (including field scale vegetables) or a mixture of arable and horticultural crops; holdings where arable crops account for more than one-third of total SO and no other grouping accounts for more than one-third.

UK food self sufficiency is at its lowest levels since 1980 and trending downwards. See more here. The figure can be measured in different ways, but using farmgate value (problematic given that we don’t eat value, we eat food) the figure stood at 58% for 2023. My feeling though is that if we focus on what people need to eat, that it’s likely worse than this, but that requires further research.